By Source (WP:NFCC#4); Wikipedia, Fair use

What is MoCA WiFi?

Longtime IAG readers are well aware of our affinity for Data Over Cable Service Interface Specification (DOCSIS), the technology delivering the Internet over coax. Many multiple services operators (MSOs)—aka “the cable company”—offer data speeds of 1 gig down with DOCSIS 3.1. But how do you get that speed from your modem to your WiFi network and connected devices? Glad you asked; let’s discover MoCA WiFi.

MoCA Is Not Coffee

We first brought your attention to Multimedia over Coax Alliance (MoCA®) in our discussion on WiFi repeaters vs. extenders. MoCA, established in 2004, is an international standards consortium composed of 22 members, including MSOs like Comcast and Cox, and gear manufacturers such as Arris and Nokia.

Three versions of the specification (MoCA 1.1, 2.0 and 3.0) are currently available; MoCA 1.0 is now deprecated. The versions you want, if you’re interested in WiFi gig speeds, are either 2.0 (1 Gbps) or 2.5 (2.5 Gbps). These speeds refer to actual throughput. All versions are backward-compatible with previous issues.

There’s also a “MoCA Access” for point-to-multipoint applications; both 2.0 and 2.5 can be deployed for use in multiple-dwelling units (MDUs) such as hotels, dormitories, hospitals, etc.

The idea behind MoCA is to use a building’s existing coax wiring as a WiFi extender. Most homes built within the past 40 to 50 years have coax wiring and outlets in almost every room, particularly bedrooms and common areas such as dens and parlors. Coax outlets originally accommodated cable TV (CATV) connectivity.

With MoCA, coax is repurposed from CATV to Internet connectivity. A MoCA adapter connected to a DOCSIS modem links to another adapter located elsewhere on a coax network. While not quite as good as Ethernet, coax delivers faster speeds than Powerline Adapters.

MoCA solves WiFi connectivity difficulties often found in spacious homes with multiple levels. A centrally-located “volcano” WiFi router often fails to reach a home’s far corners since its range, data capacity and signal strength are susceptible to distance and barriers as well as devices such as microwave ovens that can cause signal interference.

Be aware that a MoCA adapter does not replace a cable modem.

Simple MoCA Topology

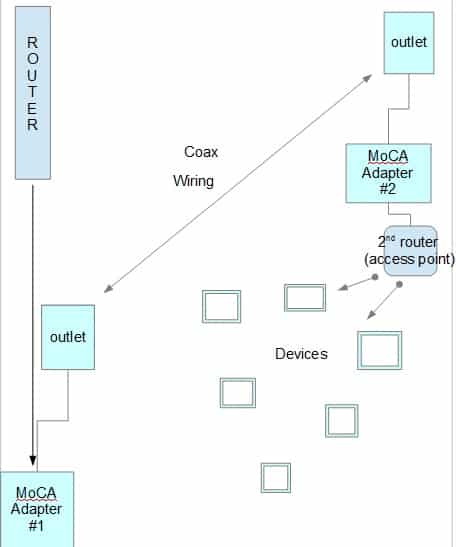

Note in the diagram above:

-

The ROUTER connects to MoCA Adapter #1 with both a coax cable and an Ethernet cable. Note if the ROUTER serves as a WiFi gateway, it’s also an access point (AP).

-

Coax cable connects outlets to MoCA adapters.

-

Coax wiring is typically found within walls of a building, often in conduits.

-

An Ethernet cable connects MoCA Adapter #2 with the 2nd router (AP).

-

WiFi connects MoCA Adapter #2 with wireless devices.

According to Motorola, most routers have MoCA out-of-the-box functionality. And some fiber optic routers have a MoCA adapter built-in. In this case, users won’t need MoCA Adapter #1 depicted in the diagram above. Look for the following logo on your router:

Fair Use per 17 U.S.C. § 107

MoCA’s impedance is designed for 75-ohm coax. Know the difference between the two types of 75-ohm coax cable typically used with MoCA: RG-6 and RG-11. RG-6 is very flexible and designed for indoor use while RG-11 is much more rigid and most often installed outdoors. Of the two, RG-11 has lower attenuation but should not be used for runs shorter than 100 feet.

Refer to this handy Alliance reference guide for MoCA home installation best practices.

If you’re curious about gear with native MoCA capability available on Amazon, visit:

-

Arris TG1682G —DOCSIS 3.0-compatible modem with speeds “up to” 640 Mbps.

-

Actiontec WCB6200Q02—”WiFi extender”; “Independent tests showed average WiFi speeds near 1 Gbps.”

-

Translite TL-MC84—MoCA 2.5 Ethernet over Coaxial Adapter (set of 2); “offers actual data rates up to 2.5 Gbps.” Reputedly UPnP.

Let’s watch the Upgrade Junkie on YouTube explain Motorola’s MoCA adapter:

The Importance of Separate SSIDs

When you use MoCA to extend your WiFi network, you’ll want to set up separate WiFi networks wherever MoCA adapters and APs are (We assume you’ll have no more than three MoCA adapters). Trust us on this.

In Motorola’s words,

“If you start walking from your main router toward the MoCA-enabled second router with your smartphone, and you start with a WiFi link to the main router, at some point you will get either a weak signal or a dropped connection. At that point, you should select the network name of the second router, and you should enjoy a better connection.”

You don’t want one set service identifier (SSID) for both networks. Why? Your “confused” devices will alternate connecting between the two APs—both with the same SSID— resulting in dropped and spotty connections. Even worse, the possibility exists that your neighbors could tap into your WiFi network (and vice versa). See this extended Reddit forum entry for more details.

My IAG colleague Benmin Smith discussed these contretemps at length here. The moral of the story? Purchase your WiFi router(s), as we’ve recommended time and again. For tips on converting your wireless router to an AP, read this article from tomshardware.com.

MoCA Splitters and POE filters

While most homes require only simple MoCA installations, sometimes a MoCA network needs modification to accommodate devices that gobble prodigious amounts of data, such as UHD (4K) TVs. In these cases, splitters are used as well as Point of Entry (POE) filters.

The idea behind a splitter is to relieve a WiFi AP’s data burden by using coax to connect to a Set-top box (STB). An HDMI cable then connects from the STB to the TV. Typically, a root (or hub) splitter connects to satellite splitters, which in turn links devices like an STB as well as an AP. See here for a sample diagram of a “complex” MoCA home installation.

If you hear the term “directional coupler” or “line tap,” know that it’s a specialized splitter providing unequal outputs to devices with varied attenuation tolerances.

POE filters are used with MoCA’s Physical (PHY) “Band D” (600 Mbps) layer. (Other PHY layers include Bands “E” and “F,” both found with MoCA 2.0 and 2.5.)

Consider a POE filter as a combination mirror and blocker. One, it reflects RF signals over 1 GHz into the home LAN, thereby boosting MoCA signal strength and improving connectivity. It also “blocks” or isolates the home network from the DOCSIS WAN. You don’t want your local MoCA network connecting to a neighbor’s coax LAN.

MoCA Limitations

Unfortunately, MoCA doesn’t work with satellite TV services (read: DirecTV), nor is it compatible with OTA TV. The reason why is that MoCA utilizes frequency bands that don’t interfere with sat or OTA radio signals. (Yes, Virginia, both OTA TV and FM radio use the same portion of the electromagnetic spectrum aka EMS.) Thus, MoCA is only compatible with CATV, Verizon’s FiOS and “off-air” TV services.

MoCA products connect via the portion of the EMS between 850-1550 MHz. However, the Alliance provides (or did provide) specialized MoCA gear for DirecTV and Dish Network. DirecTV-compatible gear works specifically for their proprietary B-band (250-750 MHz), meaning it won’t work with non-DirecTV installations. The same supposedly holds for Dish Network’s frequency bands.

ATT TV (formerly U-verse) subscribers, take note. Their paid TV service will not work with MoCA. One has to wonder when the Death Star’s recalcitrance with MoCA will affect DirecTV, recently acquired by AT&T, as well.

Coda

Trouble looms on the horizon for MoCA and those who support the standard and its evolution.

First, Alliance membership fell from 45 members in 2013 to just 22 today. Companies that have withdrawn from the Alliance include Cox Communications, DirecTV, Samsung and D-Link. Tellingly, a vendor executive claims that “MoCA is a four-letter word” at Charter Communications.

Second, while the next evolution of MoCA—MoCA 3.0, with speeds of 10 Gbps— is already past the whiteboards, some industry observers doubt it will see commercial deployment. Jeff Heynen of the Dell’Oro Group, a leading independent research firm, opines: “I think MoCA 2.5 might be the last version of MoCA we’ll see.” He adds, “It’s not a growing market.”

Why the discouraging words? It’s all indicative of the overemphasis (note writer’s editorial comment) manufacturers and consumers today place on the wireless environment. EVERY DEVICE, it seems, must have wireless capability.

While the launching of WiFi 6 (aka IEEE 802.11ax) has WiFi users salivating over the standard’s incredibly fast speeds, wireless signals are no good if they can’t reach end devices. Sometimes, you need a wire—be it coax or Ethernet—through a wall or a floor to connect to a router.

One positive note: CFO Steve Litchfield of MaxLinear (a company with a presence in both MoCA and WiFi) observed an “uptick in MoCA activity” during 1Q 2020, adding: “Wired connectivity remains an important growth driver to relieve in-home connectivity bottlenecks and our MoCA solutions will benefit from that market dynamic.”

The final word goes to MoCA’s new president, Dr. Leonard Dauphinee of MaxLinear, who notes: “WiFi technology has continued to improve performance with each generation; however, true whole home multi-Gigabit speeds are not yet possible without wired backhaul.” He adds, “MoCA is a key technology to improve whole-home WiFi coverage, speed and robustness.”